The Importance of Training for Longevity and How to Do It

Why health and fitness longevity is important

The first thing to be wary of is mobility later in life.

Once we enter our forties we're at risk of developing sarcopenia: the loss of muscle tissue and function.

And this accelerates rapidly as we age.

Letting this get out of hand is not ideal for our elder years, as activities as simple as walking become difficult!

That's no way to live.

And so, it's no surprise that resistance training together with adequate protein intake helps prevent sarcopenia.

Research shows we start losing muscle at a rate of 3-8% per decade after the age of 30, so it's obviously best to start resistance training as early as we can and keep it consistent.

And the promising news here is if we keep training, we'll keep our muscle mass. Research into world champion master athletes in their 90's found:

"...a greater number of surviving motor units, reduced collateral reinnervation, better neuromuscular transmission stability, and a greater amount of excitable muscle mass compared with age-matched controls."

So, no reversals in muscle mass and functioning if we keep training in our older age!

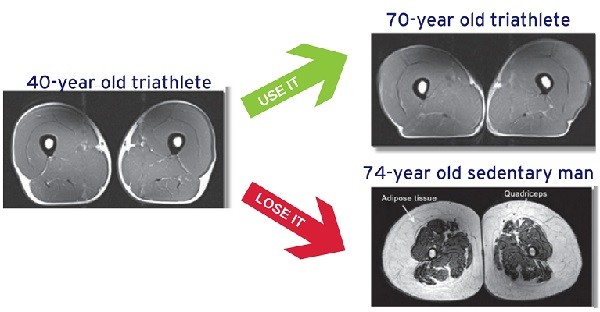

Moreover, this study into recreational athletes produced an image we can't ever forget:

The leg of a 70-year-old triathlete is the same as a young man in his 40s!

But if we do nothing (as seen in the 74-year-old sedentary example) we lose muscle mass and gain fat.

Fitness for the mind

Research proving that aerobic exercise might reduce dementia risk is rapidly growing. Moreover, resistance training decreases mild cognitive impairment, with the latter increasing dementia risk.

Moreover, it's mental health that exercise is terrific for; another reason to pay attention to training for longevity.

Physical activity assists us with depression, anxiety, and fatigue.

Situations we want to prevent for as long as possible.

Resistance training for longevity

We all realise at some point in our lives that our bodies are not invincible. Resistance training is a quick way to learn this!

We have to learn to pace ourselves and our workouts, week to week, year to year.

And a great way to do this is with "deload" weeks; where we train with less intensity. Specifically, this involves:

1. Lifting less weight

2. Performing fewer sets

3. Performing fewer reps

Deload weeks can help prevent general fatigue, injuries, plateaus, and help us get past those periods that we're not motivated to train.

Essentially, they help us to train another day. They help us with our longevity, so we're fighting fit in our older age.

We invest money for our older years, why not invest sweat into our future mobility, too?!

Turning up to perform all sets to muscle failure, and lifting as much weight as we can, is not a recipe for ensuring we live to train another day.

We must play the long game!

And if any exercise bothers you, stop doing it. It might even be worth seeking advice from a fitness professional like a physiotherapist to find out why.

There's always a workaround to certain exercises -- don't feel guilty if you can't perform anyone for some reason.

Muscle growth ceiling limit

If only we could keep growing muscle year on year!

But we know we can't.

Leading researchers say that whilst there's no solid evidence for what our "muscle growth ceiling" actually might be, this is what we can expect:

First 6-12 months: Men can gain 9-11 kilograms of muscle, women about half of this

Second-year of lifting: You can gain half the amount you gained in your first year

Third-year of lifting: You can gain half of what you gained in your second year.

Many might argue that there's no point to training after the third year, as you stop growing additional muscle mass.

But why not KEEP the muscle gains you have, whilst benefiting from the mental health positives as outlined, and investing in the mobility of your future self?

When we examine the research clearly, the argument can be made that resistance training with your older years in mind is probably the most important reason to do it when you're younger.

Not to mention, you'll look better for the majority of your life anyway!

The bottom line is that training for longevity is very important for your quality of life in your older years. Once we enter our forties we're at risk of developing sarcopenia, the loss of muscle tissue and function, and resistance training help prevent this. If we keep training, we'll keep a lot of our muscle mass and function.

Moreover, exercise (cardio and resistance training) might help us prevent dementia, whilst assisting our mental health by helping prevent depression and anxiety. Practising deload weeks helps us preserve energy and prevent injury, so we can keep training to utilise these aforementioned benefits.

References:

- Ahlskog JE, Geda YE, Graff-Radford NR, Petersen RC. Physical exercise as a preventive or disease-modifying treatment of dementia and brain aging. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011 Sep;86(9):876-84. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2011.0252. PMID: 21878600; PMCID: PMC3258000.

- Fiatarone Singh MA, Gates N, Saigal N, Wilson GC, Meiklejohn J, Brodaty H, Wen W, Singh N, Baune BT, Suo C, Baker MK, Foroughi N, Wang Y, Sachdev PS, Valenzuela M. The Study of Mental and Resistance Training (SMART) study—resistance training and/or cognitive training in mild cognitive impairment: a randomized, double-blind, double-sham controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014 Dec;15(12):873-80. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.09.010. Epub 2014 Oct 23. Erratum in: J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021 Feb;22(2):479-481. PMID: 25444575.

- Holloszy JO. The biology of aging. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000 Jan;75 Suppl:S3-8; discussion S8-9. PMID: 10959208.

- Kiely, John. (2012). Periodization Paradigms in the 21st Century: Evidence-Led or Tradition-Driven?. International journal of sports physiology and performance. 7. 242-50. 10.1123/ijspp.7.3.242.

- Power GA, Allen MD, Gilmore KJ, et al. Motor unit number and transmission stability in octogenarian world class athletes: Can age-related deficits be outrun?. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2016;121(4):1013-1020. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00149.2016

- Resnick HE, Carter EA, Aloia M, Phillips B. Cross-sectional relationship of reported fatigue to obesity, diet, and physical activity: results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006 Apr 15;2(2):163-9. PMID: 17557490.

- Rethorst CD, Wipfli BM, Landers DM. The antidepressive effects of exercise: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Sports Med. 2009;39(6):491-511. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200939060-00004. PMID: 19453207.

- Robinson S, Cooper C, Aihie Sayer A. Nutrition and sarcopenia: a review of the evidence and implications for preventive strategies. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:510801. doi: 10.1155/2012/510801. Epub 2012 Mar 15. PMID: 22506112; PMCID: PMC3312288.

- Walston JD. Sarcopenia in older adults. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24(6):623-627. doi:10.1097/BOR.0b013e328358d59b

- Wipfli BM, Rethorst CD, Landers DM. The anxiolytic effects of exercise: a meta-analysis of randomized trials and dose-response analysis. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2008 Aug;30(4):392-410. doi: 10.1123/jsep.30.4.392. Erratum in: J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2009 Feb;31(1):128-9. PMID: 18723899.

- Wroblewski AP, Amati F, Smiley MA, Goodpaster B, Wright V. Chronic exercise preserves lean muscle mass in masters athletes. Phys Sportsmed. 2011 Sep;39(3):172-8. doi: 10.3810/psm.2011.09.1933. PMID: 22030953.