Alcohol - A good time or your Achilles’ heel?

Ethyl Alcohol

Ethyl alcohol (or ethanol), as it's called, is what you'll find makes alcoholic drinks alcoholic. For most, this is common knowledge. What you may not know is how it fits into the realm of nomenclature, nutritional value, and metabolism. Ethanol closely resembles the molecular structure of a carbohydrate however its metabolism is more like that of fatty acids. Ethanol (which I will continue to refer to as alcohol) doesn't necessarily serve any useful purpose in the body, which can be thought of as 'empty calories. The calorie value of 1g of ethanol (alcohol) yields 7 calories of energy.

Practically speaking, if you had 1 standard drink (which contains 10mL of alcohol you would be consuming 70 calories) - and that’s if you had it as a shot or mixed with water. You may have heard the term empty calories before but struggled to interpret what this means. Empty calories refer to a nutrient that is devoid of nutritional value. Let's be clear straight away, the nutritional value is a different concept to that of social value - as alcohol is commonly used in society as a means of engagement between people; from the Royals in England, tradespeople at the end of a work week, or in the sports shed after a sporting fixture.

Biochemistry and Your Metabolism

The body absorbs alcohol quite efficiently, throughout the entire gastrointestinal tract.

It then moves into the bloodstream and then primarily taken to the liver and a lesser degree, other tissues around the body. In small quantities, the physiological effects of alcohol on the body are quite subtle. However, excessive and regular consumption have quite profound effects. Excessive consumption of alcohol can lead to alcoholism. Alcoholism is defined by the National Could on Alcoholism as "consumption that is capable of producing pathological changes" (Gropper and Smith, 2013) and is the third leading preventable cause of death (Mokdad et al., 2004).

The most commonly known causes of alcoholism include fatty liver, hepatic disease (cirrhosis), lactic acidosis, and metabolic tolerance. All of which is a result of how alcohol is metabolized in your body. Essentially, the normal metabolic pathways become compromised and result in acetaldehyde toxicity, elevated NADH: NAD+ ratio, metabolic competition, and induced metabolic tolerance (Gropper and Smith, 2013).

Moderation - Truth or Fallacy? Let’s Open It Up to Discussion

When someone approaches me with their confident notion of moderation and alcohol consumption I find it tricky to present only a dichotomous view of ‘agree’ or ‘not agree’. My usual response is - ‘do you know how much a standard drink of alcohol resembles?’. I very rarely get someone who knows exactly how much this is. There has been some research of an inverse relationship between alcohol consumption and coronary heart disease and evidence to support positive effects of alcohol or wine intake on oxidative stress, insulin sensitivity, diabetes mellitus, and inflammation (Ferreira and Willoughby, 2008). What’s important to recognise though is the quantity of alcohol being consumed and it's electrolyte composition as mentioned in the Journal of Applied Physiology; Journal of Sports Nutrition and Metabolism; and Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism(Desbrow et al., 2014, Desbrow et al., 2013, Shirreffs and Maughan, 1997).

There is also some recent evidence that came to light indicating that there is no level of alcohol that improves health (Burton and Sheron, 2018). Therefore, conversing on the topic of alcohol can be tricky based on the variety of evidence presented. However, depending on an individual's goals, it can also be quite straightforward (eg: muscle protein synthesis)... but I’ll leave that for a later section of this article.

How alcohol can affect sport performance

As alcohol has a calorie basis (7kcal per gram) it can be used as a fuel source. However, it is metabolised relatively slowly in the liver at only 10g/hr. Due to one of the metabolic pathways it follows (by way of acetate in the liver), it is used slightly differently as a fuel source as compared to fat. As previously mentioned, I alluded to the fact that alcohol is metabolized similarly to fat, but here is a couple of reasons as to why it is not the same- some of which you may or may not already know (bear with me, sorry to throw a spanner in the works)... Alcohol may make an individual, or in a sporting context, an athlete - feel good. However, this athlete won’t necessarily perform any better. For instance, alcohol can be used by shooting athletes to steady their hands (don't worry.. this trick won't be used by your surgeon) however, there is usually a regulated limit as to how much alcohol can be consumed for this purpose during an event. The example I want to hone in on specifically is the fact that alcohol is a vasodilator of blood vessels.

It accelerates heat loss in the skin. Therefore, an athlete such as a triathlete doing an open sea swim - may be prone to hypothermia (Kouris-Blazos, 2011). Now let’s put this vasodilation scenario into a more general population (non-triathlete) demographic. If an individual consumes alcohol in an environment where they cannot manage their core body temperature efficiently (eg: cold climates) these people too, may be susceptible to illness if their body temperatures drop too low.

Diuretic effect

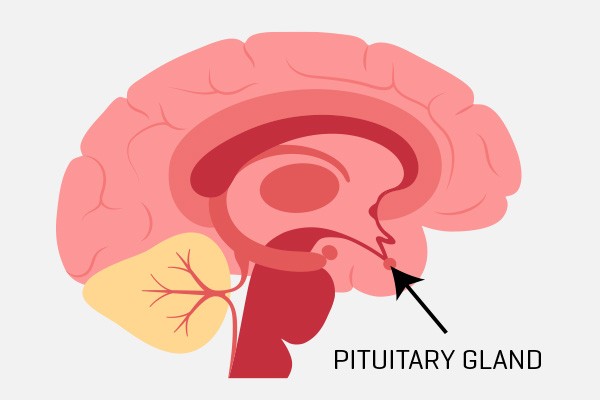

Now for some [a tiny amount] of anatomy. In the middle of your head, there is a part of your brain called the hypothalamus that works with a neighbouring endocrine gland called your pituitary gland.

They are located just inferior to your frontal lobe and sits roughly halfway between that and the pons of your spinal cord. The pituitary gland stores a hormone called antidiuretic hormone (ADH) after it is made in the hypothalamus. ADH communicates with your kidneys and lets them know how much water to conserve. Alcohol muddles up this mechanism by inhibiting ADH. In simple terms, alcohol stops the release of ADH. ‘Anti’as the prefix, refers to opposition or against the effect, therefore anti-diuretic hormone.

Once you stop the mechanism that controls the flood gates [ADH]... hello increased toilet trips. One very interesting conclusion from a paper published by Hobson and Maughan (2010) was that the effect of alcohol and its diuretic effect was blunted when their study participants were in a fluid deficit (think of this as being dehydrated). This is an interesting phenomenon and suggests the number of toilet trips a person may need to make when consuming alcohol depends on how hydrated they are. Therefore, if a person is dehydrated and consumes alcohol that person may go to the bathroom less. Sure.. this might sound convenient but dehydration is never something you want to strive for. I believe this now ‘segways’ nicely into the next subtopic, recovery.

Alcohol's effect on recovery after sport

In modern times, alcohol has become a huge component of some sports. This has become evident through many testimonials and media coverage on binge drinking by some athletes after their competitive season ends (Barnes, 2014, Burke et al., 2003, Maughan, 2000, O'Brien and Lyons, 2000, O’Brien et al., 2005). One of the greatest effects alcohol has on the human body and mind, is impaired judgement and decreased levels of inhibition. There is a potential for high-risk behaviours, accidents and injuries and sometimes death. Without being too bleak this is the unfortunate side to alcohol consumption, with the severity of these scenarios exacerbated by increased consumption. There has, over the last 2 decades been some research to show that there is a high correlation between alcohol consumption and drowning, spinal injuries and other problems in recreational water activities (O'Brien, 1993, O'Brien and Lyons, 2000). Another consideration is that when an individual becomes intoxicated it is likely that they will become distracted from appropriate recovery strategies including nutrition, injury treatment and sleep (Burke and Deakin, 2015). These considerations become more important to maintain when an individual is regularly active or participates in strenuous exercise/is a competitive athlete.

Further considerations of alcohol consumption are its ability to impair optimal rehydration after a fluid deficit (and/ or dehydration) as previously mentioned and glycogen storage. However, with the latter what's a greater chance of occurring is insufficient amounts of carbohydrate being consumed when it is needed then to the lesser degree the impaired glycogen storage effect. Additionally, is the concept of RICE - after a soft tissue injury. Which often occurs in many contact- (and some non-contact) sports. For those who don't know - RICE is an acronym for Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation. Since alcohol is a vasodilator of cutaneous blood vessels, it's been suggested that when alcohol is consumed in larger amounts it might create or exacerbate swelling around said damaged tissues and might impair proper healing.

Unfortunately, there is currently sufficient systematically studied evidence to support this, however, there have been case studies that identify these findings. An article written by Barnes (2014) talks a bit more about this recovery issue when alcohol is consumed. This article reports alcohol’s effects and recovery and considers anti-inflammatory responses, immune parameters, endocrine systems, vascular blood flow and the quantity and quality of sleep. Sidenote, you might like to check out a separate article I have written about inflammation specifically, here.

Another paramount consideration of alcohol consumption is what it can do to our muscles. It’s been found that alcohol reduces the anabolic response of muscle protein synthesis - muscle building (Parr et al., 2014). This has been shown to still occur even when an individual consumes protein at the same time in an attempt to provide sufficient nutrients for muscle growth.

Therefore, this may impair an individual’s recovery ability post-training and hinder physiological adaptation - in turn potentially decreasing future performance output.

Summary

Different forms of exercise disrupt the bodies inherent homeostasis and/or provide an opportunity for the body to adapt to the stimulus. Consuming the right foods, in the right amounts, at the right times can help bring back this homeostasis to suitable balance and performance levels or simply optimise the adaptation process. This return to homeostasis can be facilitated by providing a means of restoring your muscle and liver fuel stores (eg: glycogen), bringing you back to a hydrated state (from a fluid deficit), and provide a new opportunity for muscle growth (protein synthesis). Alcohol can be detrimental to these processes as we have discussed throughout this article.

It’s important to continually be educated about what we are putting into our bodies, in what amounts, and at what times of the day and when it revolves around a training schedule. Alcohol consumption doesn’t need to be abstained from in my opinion however the evidence proposed above about the effects of alcohol are validated through the aforementioned evidence based research. If an individual can actively and effectively regulate their alcohol consumption they can still quite possibly achieve the quality of life they want and obtain positive training adaptions. However, many factors need to be in place first such as adequate nutrition, good sleep hygiene, a commitment to regular physical activity, regular water consumption and high levels of commitment and discipline. Which is all easier said than done.

Max Cuneo is a physiotherapist, nutritionist and sports trainer with a passion for health and wellbeing. He has competed in many sports including sailing and bodybuilding, and is working towards his Masters in Public Health.

More about Max CuneoReferences:

- Barnes, M. J. 2014. Alcohol: Impact on Sports Performance and Recovery in Male Athletes. Sports medicine (Auckland), 44, 909-919.

- Burke, L. & Deakin, V. 2015. Clinical Sports Nutrition, Australia, McGraw-Hill Education.

- Burke, L. M., Collier, G. R., Broad, E. M., Davis, P. G., Martin, D. T., Sanigorski, A. J. & Hargreaves, M. 2003. Effect of alcohol intake on muscle glycogen storage after prolonged exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 95, 983-990.

- Burton, R. & Sheron, N. 2018. No level of alcohol consumption improves health. The Lancet, 392, 987-988.

- Desbrow, B., Jansen, S., Barrett, A., Leveritt, M. D. & Irwin, C. 2014. Comparing the rehydration potential of different milk-based drinks to a carbohydrate–electrolyte beverage. Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism, 39, 1366-1372.

- Desbrow, B., Murray, D. & Leveritt, M. 2013. Beer as a sports drink? Manipulating beer's ingredients to replace lost fluid. International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism, 23, 593-600.

- Ferreira, M. P. & Willoughby, D. 2008. Alcohol consumption: the good, the bad, and the indifferent. Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism, 33, 12-20.

- Gropper, S. & Smith, J. 2013. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism, Belmont, CA, Yolanda Cossio.

- Hobson, R. M. & Maughan, R. J. 2010. Hydration Status and the Diuretic Action of a Small Dose of Alcohol. Alcohol and alcoholism, 45, 366-373.

- Kouris-Blazos, A. 2011. Nutrition for activity, sport, and survival, Crows Nest, NSW, Allen & Unwin.

- Maughan, R. 2000. Nutrition in sport, Osney Mead, Oxford, Blackwell Science.

- Mokdad, A. H., Marks, J. S., Stroup, D. F. & Gerberding, J. L. 2004. Actual Causes of Death in the United States, 2000.JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association, 291, 1238-1245.

- O'brien, C. P. 1993. Alcohol and sport. Impact of social drinking on recreational and competitive sports performance. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 15, 71-77.

- O'brien, C. P. & Lyons, F. 2000. Alcohol and the Athlete. Sports medicine (Auckland), 29, 295-300.

- O’brien, K. S., Blackie, J. M. & Hunter, J. A. 2005. Hazardous drinking in elite New Zealand sportspeople. Alcohol and alcoholism (Oxford), 40, 239-241.

- Parr, E. B., Camera, D. M., Areta, J. L., Burke, L. M., Phillips, S. M., Hawley, J. A. & Coffey, V. G. 2014. Alcohol ingestion impairs maximal post-exercise rates of myofibrillar protein synthesis following a single bout of concurrent training. PloS one, 9, e88384-e88384.

- Shirreffs, S. M. & Maughan, R. J. 1997. Restoration of fluid balance after exercise-induced dehydration: effects of alcohol consumption. Journal of Applied Physiology, 83, 1152-1158.